Slavery therefore inevitably occurred everywhere in the New World (as Richard Sheridan remarked) “(a) where it has been possible to maintain slaves very cheaply; (b) where there has been an opportunity for regular recruitment through a well-supplied market; (c) in agricultural production on a large scale of the plantation type, or in very simple industrial processes”. The second point was also stressed by Claude Meillassoux, who even believed that employing slaves is only sensible when the reproduction of these involunatry servants can be delegated to foreigners. In other words, there must be a steady supply of new (adult) slaves, because there is no such thing as breeding slaves.

In Surinam, some of these conditions were initially met. It was a country with open resources, in the sense that all immigrants could have access to land in sufficient quantity for subsistence agriculture at the very least. Theoretically, slaves could be maintained cheaply by letting them grow most of their own food. In reality, however, the situation in the colony was far from ideal for a flourishing economy based on slavery. One of the major flaws of the Surinam slavery system was the neglect of food production to such a degree that a large part of the staple foods had to be imported from the United States. Since the trade routes were often blocked, this repeatedly caused severe food shortages, leading to much social unrest. The supply of slaves was erratic as well and they were comparatively expensive due to the unfavorable location of the colony outside the main trade routes. As a result, Surinam never had sufficient slaves to fully exploit the potential production capacity. Slaves were used for industrial enterprises only on a limited scale: with some benevolence one can classify the timber ‘plantation’ as such and furthermore the colony boasted a Bergwerk (mining company –a colossal failure) and the stone quarry Worsteling Jacobs.

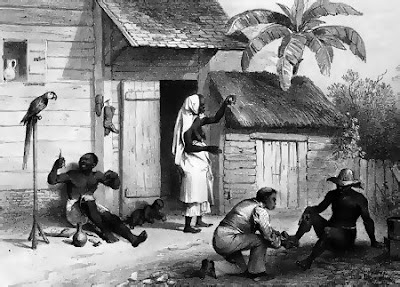

Another weakness of the Surinam slave system was the fact that a large part of the able-bodied slaves was withdrawn from productive work to idle away as house servants. Having a large retinue, even if totally unproductive, can serve a worthwhile purpose if it helps to impress the ‘poor whites’ so much that they will fight to preserve a system that is harmful to their own interests. According to Eugene Genovese, this was the case in the Old South. In Surinam, such a display of conspicuous consumption was useless.

As Pieter Emmer claimed, the Dutch would undoubtably have been better off if they had stuck it out in New York and had left Surinam to the English. Unfortunately, Abraham Crijnssen and his men were not clairvoyant and after conquering the colony and having been allowed to keep it, they had little choice but to expand the system of plantation agriculture they encountered. This inevitably implied importing additional slaves.

Much of the work that had to be done in Surinam could be done by whites and in the early years often was, but there was a firm belief among the colonists that no European could stand fieldwork in the tropical heat, so there was a reluctance to let even convicts toil in the fields. Indian slaves were apparently never used for cultivation either, but were only employed as house servants, fishermen and hunters. So it can be safely assumed that until emancipation all agricultural labor was performed by Negro slaves.

Practically all the slaves outside Paramaribo (which amounted to at least 80% of the slave population) were involved directly or indirectly in plantation agriculture, but a mere minority was actually sent into the field. Kuhn calculated in a gloomy mood that only one third of the slaves could be regarded as “truly capable of work”. Most observers agreed that having a field force of about 40% of the total slave force was a favorable situation. Van der Smissen, for example, distinguished a ‘general force’, a ‘workforce’ (consisting of about 60% of the general force) and a ‘field force’ (consisting of about 40% of the general force). Pistorius divided the slaves of a hypothetical sugar plantation with 125 hands as follows: 58 field hands (48%), 26 drivers, artisans and house servants (20%) and an unproductive group consisting of children, invalids and old people (32%). Van den Bogaart and Emmer found in the actual case of the sugar plantation Catharina Sophia an unproductive group of 29%, a field force of 54% of the able-bodied men and 78% of the able-bodied women, while 25% of the men and 9% of the women were in the ‘elite’ category.

The numbers mentioned by Van den Bogaart and Emmer indicate a remarkable contradiction. It has been maintained that the slaveholders preferred male slaves because they were stronger and more productive in the field, yet they were also believed to be more versatile and positions requiring leadership or skills were almost exclusively reserved for men. So an increasing proportion of the men was withdrawn from fieldwork, while women could escape the field only when they were elevated to the position of house servant. This allocation of tasks by sex under slavery was “compatible with the predominant role of women in agricultural labor in the major African societies from which the slaves came”, Higman remarked. Some ‘high-born’ men considered agricultural labor so demeaning that they rather died than stoop to it. John Stedman witnessed that sometimes their ‘inferiors’ were allowed to fill in for them, but at other times the planters were determined to show that for them African social distinctions and sensitivities had no meaning. If the unwilling persisted in their refusal, they might be killed as an example for others. It is reasonable to expect that the growing participation of women in fieldwork lowered productivity, but this was apparently not the case. Higman found that in Jamaica output actually increased during the years 1817 to 1834, when the proportion of female field hands rose sharply, and that technological innovation was not the cause.

It has been claimed that one of the main advantages of slavery was the fact that a greater part of the population could be forced to perform productive work. Perhaps this is the case if one compares the work force on a slave plantation with the proportion of people going out to work in a modern (post)industrial society. Here, the work force consists mainly of adult men who support their wives and children and, by paying taxes, the aged, sick and handicapped as well. But this has no parallel in a traditional agricultural society, where women and older children are heavily involved in the production process and where the percentage of inactive people is a lot smaller.

It cannot be maintained that in this sense the slave population was exploited to an exceptional degree. The women were perhaps granted less time to care for their families, but some tasks were taken over by others (for example the crioromama and the dresneger). As for the children, they were not obliged to help out more than they would have been in African societies. The planters usually took care to spare them real hardship until they were fully grown. Blom remarked on this subject: “[slaves] are counted among the children, as long as they do not go into the field or perform their craft independently; for this they have to be about 18 or 20 years old; before that they are used for lighter work and as their powers increase the workload is augmented.”

The main difference with a traditional agricultural society was the fact that the elders were not allowed to enjoy the remainder of their years in peaceful rest, cared for by their children, but that they had to serve in one capacity or another for as long as they had any strength left, as nurse, guardsman, gardener, etc. Furthermore, ailing slaves were sometimes forced to work anyway –a self-defeating kind of efficiency. There is no evidence that the division of labor shifted significantly after the first quarter of the 18th century and the allegation that the exploitation of the slaves increased during the 19th century, because a larger percentage of the slaves was sent into the field, is unsubstantiated.

Employing bondsmen hampered technological innovation. The primary means of increasing productivity was increasing the workload of the individual slave. One of the main charges against the slavery system has always been the claim that slaves were systematically overworked. It has even been claimed that sometimes slaves were literally ‘worked to death’. In Surinam this was certainly not the case. Of course there is ample evidence that the burdens of Surinam slaves were often heavy. Blom, for example, complained that “right now the negroes on many plantations have to work more than their strength allows in the long run”. Surinam slaves were undoubtedly exploited in two senses: (a) with regard to the (monetary) compensations they received for their efforts and (b) with regard to the food, clothing and shelter they received to make these efforts possible. However, all (agricultural) laborers were exploited during this period and the question is whether slaves were exploited more than free people in similar jobs.

It is difficult to evaluate the productivity of the slaves properly because one has to depend on the observations of prejudiced whites. These often did not have a proper yardstick for measuring their accomplishments, since many agricultural tasks were performed exclusively by slaves in Surinam and had no parallel in Europe. Bearing these limitations in mind, it is nevertheless remarkable that most authors, whether contemporary or modern, agreed that slaves may have worked long hours, but that their productivity was low and were convinced that white laborers would have been able to do the same job in considerably less time.

Even Governor Mauricius, no fan of the colonial whites, wrote to the directors of the Society of Surinam that “a white worker in Europe does more than four negroes”. His successor Crommelin observed that one white carpenter could replace three Negroes. Lans considered the work of slaves much less tiring than that of a European day laborer. Van der Smissen believed that a Dutch agricultural worker could dig, in much less time, twice as many meters of ditch as the average slave. Hostmann concluded that a willing Negro could do the tasks demanded of him in less than half the time allotted for them, in which case he could use the rest of his time according to his own discretion. Finally, Kappler, who had employed slaves, free Negroes and men from Württemberg at his lumber project on the Marowijne, remarked that if one followed the official norms, the slaves only had to saw 60 feet of timber a day, while his white lumberjacks could saw, without undue exertion, 130 feet a day. Moreover, they could clear provision grounds as fast as the slaves, although the work was unfamiliar to them.

One has to treat these observations with a measure of reservation, but they are corroborated by the conclusions of Michael Craton, who evaluated the performance of Jamaican slaves. He employed a more objective yardstick, but still found that the slaves only did about a quarter of the work commonly accomplished by modern agricultural laborers. He added that this “was almost certainly due more to unwillingness to work than to physical incapability”. Slaves got away with it because the planters did not expect much of them, as Genovese explained: “Since blacks were inferior, they had to be enslaved and taught to work; but, being inferior, they could hardly be expected to work up to Anglo-Saxon expectations. Therefore, the racist argument in defense of slavery reinforced the slaveholders’ tendency to tolerate, with an infinite patience that amazed others, a level of performance that appalled northern and foreign visitors.“

So the conclusion that the slaves succesfully resisted being driven beyond their strength seems justified. The planters failed miserably in their endeavors to extract the maximum amount of work from their slaves most of the time. During the harvest season, however, the situation was radically different. Many plantations were short on hands then and the workers were driven mercilessly. This was aggravated by the fact that on sugar plantations with a water mill it was necessary to use every available moment during springtide, so the work went on night and day.

The working hours of the slaves were limited partly by external factors. Generally, work could only be done during daylight, except when sufficient moonlight made night work feasible, which in Surinam was not very often the case. Work in a sugar mill or a coffee shed could of course continue by the light of torches or candles. Field slaves in Surinam usually labored from sunup to sundown, which was almost invariably a twelve hour period. They rose at about five o’clock, went into the field at six and paused for breakfast for half an hour at nine. During the hottest time of the day, they enjoyed a ‘siesta’ of 1½ to 2 hours. They returned from the field at about six in the evening. Consequently, their working day ordinarily lasted 10 hours at most. After the backbreaking fieldwork, they were occupied for an hour or more with cooking meals, washing clothes, working on their plots, etc. Surinam estates lacked the communal meals served at some American plantations, which saved the slaves much time and effort, but also undermined family life. Little time for relaxation was left for that reason.

As faithful Calvinists, most planters were bound to observe the Sunday rest and this obligation extended to their slaves. The first orders to observe the Sabbath dated from 1669. They mostly referred to the consumption of alcohol on this day, but a placard issued in 1674 expressly forbade “any labor [or] trade”. In 1721, the planters were specifically interdicted for the first time “to have any work done by themselves or their slaves, be it in the field, in the mill or elsewhere”. Later, some exceptions were made: on sugar plantations the planters could boil likker (cane juice) until nine o’ clock in the morning, while on coffee grounds it was permitted to let the slaves dry and sort coffee until seven o’ clock in the morning. At first, the slaves of the Jews were expected to observe the Christian Sabbath as well, but as they already had to refrain from work on Saturdays, their excess of leisure time incensed the slaves of the Christians, so this rule was relaxed soon.

Despite these regulations and the protests of pious men, many planters put the fattening of their purse before the saving of their soul and forced their bondsmen to toil on Sundays anyway. The slaves that had not completed their weekly assignments by Saturday evening were obliged to finish them the next day and sometimes slaves were directed to clean their houses or tend their gardens in the morning. Not many planters dared to tamper with their free afternoon, but exceptions were made during harvest time. Ideally, the slaves were compensated with some free weekdays later.

So in theory, the planters had unlimited rights over the labor of their slaves, but they realized that little was gained by driving them to exhaustion and earning their unmitigated enmity. For economic reasons alone, they knew they were well advised to give their slaves a little leeway.

The work ethic of the slaves.

The attitude of the slaves with regard to the work demanded of them was determined in large part by their opinion about the system that had swallowed them. The slaves compared Surinam slavery with the kind of slavery they were familiar with at home. In Africa, slavery primarily meant domestic servitude. A slave might be forcibly torn away from his home and his family, be humiliated and mistreated, but he was not alienated from his owner as profoundly as in the New World. He was usually adopted into the entourage of his master. Sometimes, he was even allowed to wed a member of the latter’s family and in that case, his descendents were born free. Africans knew that everyone could be degraded to slavery and therefore a slave was not considered an inherently inferior or depraved person. Many slaves were ransomed, but even when freedom was beyond their grasp, their situation improved with time: old retainers were often treated with indulgence. Slaves were obliged to labor for their masters, but the work was familiar to them –although male slaves were sometimes forced to perform tasks that were the preserve of women- and the pace was relaxed. The position of female slaves in practice often hardly differed from that of free women. A negative aspect of the situation of African slaves was the fact that they were ‘kinless’ in a society where kinship roles played a pivotal role. The greatest threat they faced was the possibility that they might be sacrificed to appease a god, or at the funeral of an important king or chief.

The economic exploitation of slaves under these circumstances was limited and cannot be compared to the kind of subjection found in societies with ‘industrial slavery’. Nevertheless, as Lichtveld and Voorhoeve concluded: “The slaves themselves … accepted slavery. They knew this form of economic exploitation of the labor force from their homeland. So they acknowledged the right of the master”. Notwithstanding this acceptance, work often takes on a special meaning in circumstances like these. Goffman has observed that in a ‘total institution’: “Whatever the incentive given for work … this incentive will not have the structural significance it has on the outside. There will have to be different motives for work and different attitudes towards it”.

In this era the prime motive for work for a free laborer was pure economic necessity. He had to gain the daily bread for himself and his dependants, or he would perish. For a slave, this was only partially true. A slave was a valuable asset for his master, so he usually received food and shelter whether he worked or not –at least for a certain period. A slave owner would protect his investment as long as he expected a profit in the end. Only when the slave steadfastly refused to work and thereby demoralized the rest (in other words, when he literally became more trouble then he was worth) and the master could not profitably sell him on, he might be tempted to sacrifice him as an example to the others. A superannuated slave did not represent a potential profit anymore, so some planters decided to turn them loose and let them fend for themselves. The authorities were vehemently against this practice, since these slaves often became a burden on public funds and their relatives and friends were likely to take offense and confront such a calculating planter.

The slaves were inspired by the example given by their masters -and that was not very inspiring. John Gabriel Stedman has vividly described a typical day in the life of a typical Surinam planter. Our man rose at six o’clock in the morning and went to the verandah where his coffee and pipe awaited him. He was served by at least a dozen of the most beautiful slaves. After the morning snack, the overseer arrived to report on the progression of the work, the number of slaves who had disappeared, fallen ill, died, or recovered, who had been sold or born. The slaves who had not performed their work to satisfaction, who had feigned illness, or had been drunk were presented. They were tied to the posts of the verandah and soundly whipped. Then the dresneger came to report and was sent off with a curse, because he had allowed some slaves to fall ill. Next the crioromama arrived with the children, who had been freshly bathed in the river. They greeted their lord by clapping in their hands. The owner sent them away for a breakfast of plantains or rice. After all this exertion, the master departed on a little promenade, dressed in a morning frock of the finest linen. He strolled around the house on his ease, or went to inspect the fields on horseback. About eight o’ clock, he returned. When he planned to go on a visit, he changed clothes, otherwise he retained his morning frock. In the former case he replaced his trousers with a sturdier pair and a Negro boy put his shoes on. Others combed his hair and shaved him, while a fourth chased off the mosquitoes. He was escorted to his tentboot by a boy with a parasol. The boat had already been stocked with wines, tobacco and fruits by the overseer. If the planter decided to stay at home, he sat down to breakfast at ten o’ clock and consumed a profusion of delicacies: ham, smoked tongue, fowl or boiled pigeons, plantains, sweet cassava, bread, butter, cheese, etc, which he washed down with beer, Madeira or Moselle wine, or champagne. The overseer was allowed to keep him company. Afterwards, the planter relaxed with a book, played billiards or chess, till he retired for a siesta in his hammock, where two Negroes fanned him constantly. At three o’ clock, he awakened, washed and perfumed himself and positioned himself at the table again for the noon meal, which featured the finest dishes the country could supply. The meal ended with coffee and several glasses of liquor. At six o’ clock, the overseer came to report again and the whippings start anew. The planter gave his orders for the next morning and spent a delightful evening drinking punch or sangriss, playing cards and smoking. Between ten and eleven, he was undressed by his valet and retired to his hammock with his concubine. No wonder that, with these epitomes of diligence as an example, the slaves refused to exert themselves unduly.

Since a slave was worth money not only because of what he made, but also because of what he was, some slaves managed to excuse themselves from performing their tasks competently or even at all without serious repercussions. Many a slaveholder had to endure sloppy work and malingering to an extend that any employer of free men would have found unacceptable. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to assume that the slaves acknowledged that their master had the right to expect a fair amount of work from them. All the more as it will not have escaped them that he could not provide them with their coveted distributions if he did not have a cash crop to sell. However, the opinions of masters and slaves differed fundamentally on the question of what constituted a ‘fair amount’ of work.

Many white observers have described the Surinam slaves as lazy and inept. Lammens, for example, who (for a member of the master class) made a reasonably objective witness, lamented: “the negro is slow and lazy … the slaves always have to be prodded and stimulated: -it is an eternal and daily work to point out to them what they have to do and how they have to do it: -their general disposition is to be as incompetent as possible and to have no time: - never a negro shall try, if he can perform a task, that he does not do daily: -he begins with stating in advance that he does not know how to do it, or is unable to do it: -the slave is busy for an hour with something, that can be done by a European servant, in a quarter of an hour: - he shall never carry two objects at the same time, but rather walk three times than one: - charge him with a certain job, and fail to check it every day: certainly you will find everything neglected.” Slaves scorned dilligence and not only among themselves: Herlein claimed that “it seems that the Slaves do not even respect industrious Christians”.

A few authors, however, were well aware of the fact that the slaves did not mind working hard at tasks they enjoyed. Hostmann concluded that rowing, tiring though it might be, pleased the slaves enormously: “the steady change of places and objects counterbalances the greatest exertion, and with amazement one sees, how Negroes can keep this up for days”. Woodcutting, fishing and hunting were popular jobs as well and Hostmann therefore concluded that “distaste of all those activities, that demand a steady, regular and ceaseless labor, prevails among the Negroes beyond all understanding”. Such repetitive, monotonous tasks were, of course, found most frequently in agricultural labor and in Africa were delegated as much as possible to the people with the lowest status: the young, the women and the slaves.

Some authors blamed the climate for the slaves’ reluctance to work and pointed out that the whites were affected even worse. Teenstra observed that “Surinam is because of a blessed climate and a fertile soil so rich in noble varieties of plants and fruits, that nature offers of its own accord, without any human help, to the indolent inhabitants, that this mildness stimulates the lazy carelessness greatly and paralyses all diligence and industry”.

Kuhn acknowledged that the lack of enthusiasm for new inventions among slaves was usually well-founded: “It is generally professed, that the Negroes cannot be persuaded, to use new tools: it is true, the negro rather sticks to the old; but this is induced primarily by mistrust, and by the supposition, that the goal is not, to contribute to his ease, but to oblige him to perform more work”. Blom partly concurred, but he also doubted the good sense of some slaves: “[They] are much attached to their habits, and it is difficult to habituate them to others, even then when these would contribute to lighten their labor; they are used to carry everything on their head, this has spurred more than one Planter to try to introduce the wheel-barrow on the plantation; as long as a white was present they did not dare to refrain from using it, but he was barely out of sight, or they put the full wheel-barrow on their head, and did their work this way”. This conservatism fed by mistrust certainly complicated the work of the slaves. Von Sack observed with amazement how they would poke holes for the cotton seeds with their fingers, instead of using a digging stick (a common enough item in Africa), so they got back pain from stooping all the time.

The consequent sabotage of innovations by the slaves was the main reason that the tools used in the colony remained rather primitive. To mention but one case: the hoe was never replaced by the plough. Mrs. Boxel, owner of the plantation by the same name, sent a plow to the colony as early as 1735, but the reception was cool. Even in the 19th century, the plow remained conspicuously absent and Von Sack bemoaned this archaic situation, because the flat fields were so eminently suited to the use of a plow. Surinam was of course handicapped by a lack of draught animals, as Van der Smissen pointed out, but he too identified the opposition of the slaves as the prime obstacle for technological advancement.

Some planters used physical force freely in their attempts to prod the slaves to do more work. It was not an effective way to stimulate productivity, however. Firstly, this would have necessitated a large number of supervisors and these were not available in the colony. Secondly, they had to be totally ruthless, for it is only possible to get a maximum amount of work from slaves by force if one transforms the plantation into a kind of concentration camp. [For this reason, blacks could not adequately fill these positions. Despite the fact that some of them did not hesitate to apply the whip liberally to the backs of their fellow slaves, they were too dependent on them socially to face the risk of total alienation.] Thirdly, too great a show of force demoralized the slaves and fueled their desire for revenge. At the very least, it prompted them to try their luck in the forest. A more subtle system of punishments and rewards was needed to ensure more than the absolute minimum of work.

Officially, the slaves had few, if any, rights. Only in the 19th century, the Dutch government produced formal regulations with regard to food, clothing, workload and punishment. But, as in any totalitarian system, soon unwritten rules were established that defined certain minimal rights. The masters liked to pretend that these were privileges that had to be earned by faithful toil, but the slaves knew better and took offense when their established rights were trampled on. To stimulate diligence, the masters awarded genuine privileges that went beyond the limits set by the unwritten rules and that were sometimes branded as illegal by the authorities. They hardly ever tried to influence productivity directly by giving bounties, overtime pay, letting slaves compete for prizes, promising promotion or even eventual freedom (as some planters in the Old South did). Instead, they granted their slaves the opportunity to gain money by the sale of surplus products, did not object to frequent visits to other plantations, allowed them to have dance parties much more often than the law permitted, let them hunt with rifles and turned a blind eye to infractions of the plantation rules –in short, gave them some ‘elbow room’. A humorous example of ‘turning a blind eye’ was given by Bartelink. When Mr. Kilian, director of the plantation Potribo, noticed that the work was not going very well, he suggested to his blankofficier (Bartelink himself) to come along on a visit to the neighboring estate Concordia, explaining “Do you know what is wrong with them? They want to steal, and I will give them the opportunity to steal; therefore we go away together. If they have had their way, they will work twice as diligently.”

The most elaborate form of this ‘privilege system’ could be found on the timber grounds. There the possibilities for effective supervision were limited, because the slaves often had to work far from the homestead and stayed in the forest for most of the week, without the slightest interference from their superiors. If dissatisfied, they could escape with the greatest ease, so they were taxed lightly. In addition, they were also granted much time to work their own plots and they were allowed to market the surplus and spent the money the way they saw fit. The outer boards of every tree they felled were theirs as well. Sometimes, they were even awarded the exclusive rights to certain kinds of wood (for example letterhout) and if the masters needed this wood, they had to buy it from their own slaves.

Withdrawal of privileges (for example limiting social intercourse) was considered a severe punishment by the slaves. Therefore, it was often a much more effective way of keeping them in check than the use of the whip. In their turn, the slaves were keenly aware of the fact that refusing or sabotaging work was the best strategy to hurt the master. Hence, they often threatened to run off if they did not get what they wanted and a little demonstration of their ability to bring the plantation business to a grinding halt was often enough to make a planter capitulate.

So it can be concluded that the level of productivity of the slaves reflected a compromise between the demands of the masters and the obstruction of the slaves and since the resilience and the abilities of the parties varied from place to place, the results also did.

Regulation of the work.

Despite their reputation for anarchism in agricultural matters, the Surinam planters usually ran a tight ship. The French traveler Malouet was struck by the “uniformity in order and method in the distribution and the execution of the tasks”. In Surinam the task system was prevalent, because as a result of the lack of supervising personnel the slaves had to work on their own most of the time, guided only by the Negro bastiaan (driver).

The gang system, as it was in use in the Old South and Jamaica, was not suitable. It could lead to a better performance, but required constant attention. In such a system there were usually three gangs: a ‘first gang’, consisting of the prime field hands, who performed most of the heavy labor; a ‘second gang’, consisting of elderly and sickly slaves, plus the recently delivered women, who did the less strenuous jobs); and a third (or ‘grass’) gang, consisting of children. The members of these gangs were considered to be more or less equal in ability, so they were often positioned in (sometimes competing) rows and the strongest hands were put in front to dictate the pace. The others had to keep up as best as they could and were whipped if they fell behind.

In Surinam, all the slaves in the field force were given assignments to perform within a given period of time (day or week). Such an assignment was called a merk. These could be allotted to individuals or groups (usually consisting of 5 or 6 slaves). The size of these assigments had been determined by trial and error and consequently varied from plantation to plantation. In theory little difference was made between the capabilities of the strongest slaves and those of their weaker fellows, but when giving out tasks the planter had to take into account that his workforce did not solely consist of prime hands. If they did not get enough time to finish their tasks, the weaker slaves would be chronically behind schedule and this would lead to frustration and disturbances. So the planters were inclined to take the performance of the average slave as a guideline. This meant that the strongest hands could finish their assignments with the greatest ease and had ample time to tend their provision grounds, while the weakest slaves had to struggle constantly to finish their jobs in time and often had to work their plots on Sundays.

This gives perspective to the remark of an ‘anonymous colonist’, who had observed that diligent slaves could be off around two o’ clock in the afternoon, but that many of their fellows were two merken behind by the end of the week and consequently had little chance of any free time. Van der Smissen took the fact that the slaves came back from the fields singing and jesting in the evening as evidence for his contention that their workload was not particularly heavy. Since a slave had to be near death to stop singing, this proves little, but in all probability slaves without handicaps were not overtaxed on most plantations.

There were of course masters who were never satisfied and who abused the task system until the hands ran away in desperation. Stedman mentioned a slave called Marquis, who had worked especially hard to finish his merk early so he could tend his provision plot, only to have his master conclude that this merk had obviously been too modest (so he was ordered to dig 600 feet instead of the 500 feet originally demanded of him). Once a tradition had been established on a plantation, however, it was hard to augment the workload, as many a novice director found out. Any attempt to increase the merken met with fierce opposition of the slaves and more often than not, they were forced to back down.

In the 19th century, the Dutch government tried to regulate the size of the daily assignments formally. This was a difficult, if not impossible, job since the number of feet a slave could dig, or the amount of coffee he could pick depended very much on the circumstances. Moreover, the authorities operated on the (wrong) premise that most slaves were greatly overworked, so they tended to be excessively lenient. The merken they came up with were unacceptably small for most planters and since the means to enforce the regulations were lacking, they ignored them with impunity.

It has often been claimed that slavery tended to blur the division of labor between the sexes and as proof for this thesis the proponents pointed to the fact that men and women worked side by side in the fields and that women sometimes took on the heaviest jobs. There was of course a profound difference with the habits of farmers in Europe, but these practices reflected rather faithfully African horticultural traditions. A certain division of labor existed, even in the field. Both sexes hoed and weeded, but some tasks were almost exclusively male: such as digging trenches, felling large trees and cutting cane. Few tasks were exclusively female though; most of the jobs women were involved in were also done by (older) men and children.

Outside the field, the task system was not much in use, although a tradesman like a cooper might be ordered to deliver a certain number of barrels a week. When processing the crop, continuous work was demanded of the slaves, but it was hardly feasible to insist on a particular amount of sugar cured or berries bagged. What work had to be done was usually decided ad hoc by the supervisor. More often than in the field the slaves worked under the direction of a white, who made sure that they did not stay idle for a moment. The house slaves merely had to be at the back and call of their master, which could mean that they were sometimes busy day and night, but at other times could take it easy.

There was little specialization among the unskilled slaves. Most slaves would perform all kinds of menial jobs in the field, the mill, or the coffee shed, although some were referred to specifically as delver (digger). Of all the field hands, they were apprised the highest. If a male slave showed any promise, he was often promoted out of the field soon. Most female slaves had no such luck.

One group of bondsmen was relieved from fieldwork out of principle: the coloreds. It is not entirely clear why this exception was made. Coloreds were often considered to be less sturdy than full blacks, but lack of strength did not absolve blacks from toil in the field. It is more likely that the work was considered too demeaning for the descendant of a white, or that the masters used this privilege as a means of obtaining the loyalty of the colored group. It was an irrevocable privilege: I have found no instances of colored slaves being sent into the field as a punishment, while this often happened to privileged blacks. Because African-born slaves predominated on most plantations until the end of the 18th century and whites were discouraged from ‘interfering’ with slave women, the coloreds formed a tiny group on the majority of the plantations. Most of them ended up in Paramaribo.

Fieldwork.

Sugar plantations.

The slaves of Surinam were not very fortunate considering the work they were stuck with. A varying, but always considerable, percentage of them was employed on sugar plantations, where, as was generally acknowledged, the labor was most strenuous. Furthermore, the establishment of such a plantation was generally difficult and hazardous to the health of the slaves, due to the fact that they were often located on swampy grounds and to the necessity of harnessing the surplus of water.

The initial layout was the same for all plantations. First a suitable tract of land was selected. At the end of July or the beginning of August, the start of the long dry season, the trees were felled. To clear 20 acres of land occupied 20 slaves for three weeks. The wood was left to dry for a couple of weeks and then burned. On clay soils care was taken that the peat did not burn as well. If there was little peat, the wood was left to rot. On meager sandy soils the ashes were valuable fertilizers, so there the wood was burned methodically. The large pieces that remained were carried from the fields and the stumps were dug out. In Nickerie and Coronie the stumps were left in the field and coffee and plantains were grown between them. After the fields had been cleared, some makeshift huts were built for the slaves of pallisade wood covered with pina leaves. They could last about four years.

At the same time, the impoldering started. First, the site of the dam (surrounding dike) was chosen carefully. The peat was removed and thrown on the fields. If any was left, the dam would start leaking eventually. Then the slaves dug the loostrens (drain off trench). The clay was thrown on the dam and trampled firmly. The dam was usually 10 feet high and 10 feet wide, the loostrens 15 feet wide. Next, the land was divided into beds. They were separated by narrow trenches. The dimensions of the beds varied somewhat according to the crop, but an acre (1 ketting wide and 10 ketting long) was usually divided into three beds. In the middle of each bed a small canal called trekker was cut, which was connected to the loostrens. It was about twice as wide and deep as the trenches. The next step was the construction of a stone sluice or koker (smaller wooden sluice) on both sides of the cleared fields. They were incorporated in the dike and regulated the water level.

In the Lowlands, where water-driven mills were standard, additional waterworks were necessary. The system of canals that powered the mill was independent of the drainage system. The mill was situated at the end of the molentrens (mill trench), which extended as deep as the cultivated fields and received water from the inneemsluis (intake sluice). Other trenches (vaartrensen) were constructed on both sides of the molentrens at distances of 10 ketting apart. In front, the voortrens extended over the whole breath of the cultivated fields. These trenches served two purposes: to store water at high tide for powering the mill and to transport the cane. When water started rising during high tide, the inneemsluis was opened and the water was allowed to pour in as long as possible. Then the gates were closed and when the river had fallen about a meter beneath the level in the trenches, they were opened again. The water was directed through a brick gutter (kom) and propelled a wheel, which in turn powered the mill.

It was practically impossible to perform the sophisticated construction jobs with a crew of ‘saltwater Negroes’, so it was vital that there were some older and more experienced slaves among the workforce. The whole system demanded a considerable amount of maintenance work. According to Blom, all trenches had to be cleaned every six weeks. On the other hand, if the sluices and the mill were built sturdily and cared for properly, the system could function flawlessly for ages.

In most cases, the land was too rich (gulzig) to be suitable for cash crops right away. Sugar cane, for example, shot up sky-high on new fields. The stalks then contained little sugar and heavy rains brought them down and made them rot. Consequently, new lands served as provision grounds for the slaves during the first couple of years. In the short rainy season, the fields were prepared for planting, a job requiring thirty slaves for every 20 acres. The first crops usually consisted of tayer, plantains, corn and cassava. Care had to be taken with the latter, because it exhausted the soil quickly. After two to six years, the remnants were removed and the cultivation of the cash crop could start.

For the planting of cane, the soil was turned over with the hoe (or if there were few roots with the spade), the old ditches were filled, the beds were divided anew and new ditches were dug. Next, a rope was stretched over the breath of four or five beds and the strongest slaves dug trenches of six feet deep and nearly a foot wide. They were made at a distance of four to five feet from each other. The removed soil was spread over the beds. When the plantation was located on sandy soil or former kapoewerie land, they sometimes were narrower. The weaker slaves planted the cane. Either the tops (ratoons) or pieces of the stalks could be used, although the tops were preferred. In every trench three rows of cane were deposited, in such a way that the tops nearly touched. They were covered with a thin layer of soil and after about five days the sprouts started to show. Usually, a row of corn was planted after every two rows of cane. Three to four weeks later, the slaves started to weed and they put additional earth on top of the young plants. This procedure had to be repeated twice, after which the trench was fully filled. When the cane was about six months old, the lower leaves shriveled and were torn off (riettrassen). This work had to be done carefully: if the slaves tore off too many leaves, the stalks would wither, but if they left on too many, the sugar content of the cane decreased. This work was combined with renewed weeding and repeated every four weeks until the cane was 11 months old. Then it was left alone until the harvest.

On the high sandy grounds the cane was ripe in 15 months, in the lowlands it took three months longer. When the director decided that the moment for the harvest had come, the strongest slaves cut off the stalks close to the ground. They chopped off the leaves and the tops and threw the stalks behind them. The other slaves gathered and bound them and carried the bundles to keenponts (small flat-bottomed boats), or ox-carts (on some of the highland plantations). The leaves were left to dry for a couple of days and then burned. Some earth was thrown on the stoelen (stumps) and the plants that had died were replaced (supplyen). In the lowlands, the trenches were cleaned (modderen) after every two harvests (malingen).

When a field yielded less then 1,5 hogsheads of sugar an acre, the cane was removed, the soil was turned over and the entire process started again. This could be repeated several times, depending on the quality of the soil, but eventually the land was exhausted and then it was allowed to regenerate as kapoewerie.

After cutting the cane was transported to the sugar mill. Most mills consisted of a boiling shed (kookhuis) and a separate distillery shed (dramhuis or stijlhuis). At some distance the trashuis (shed for keeping the pressed stalks, which were used as fuel) was located, always to the east of the other buildings on accord of the prevailing winds. One side of the kookhuis was usually open. On the other side the fireplace (vuurplaats) was located. The fire was fed with cane straw (tras) or wood. The slaves who worked here often did so as a punishment and were chained to the wall. The motion of the water-driven wheel was transmitted to three presses (rolders) standing vertically. The one in the middle (the ‘king’) propelled the others. In a beestewerk, the king was put in motion by animals pulling beams attached to it. Most water-driven mills had a double set of kettles (8), while the animal-driven mills had one set (4 or 5). These were cemented onto a brick wall, with a chimney passing under them. The fire was located under the last and smallest kettle (the test), where as a result the temperature was highest. The kettles were made from red copper.

An average sugar mill employed about 26 people (more if there was a double set of kettles): 8 children, who carried the cane to the mill; 2 rietstekers, who pushed the cane between the first two rolders; 2 trasdraayers, who pushed the cane back between the second and third rolder; 1 baksielaadster, who gathered the pressed stalks; 2 onderhalers, who collected the juice; 1 voorhaler, usually a malinker (sickly slave), who cleaned the sieve; 4 trasdragers, who carried off the finished cane; 3 suikerkokers (4 or 5 when there was a double set of kettles), who supervised the boiling process; 1 (2) vuurstokers, who stoked the fires; 2 (4) trasdragers, who supplied the dried cane straw for the fire(s).

Before processing the cane, the rolders, gutters and everything else the cane juice (called likker or lecker by the whites and lika by the slaves) came into contact with had to be cleaned thoroughly, because the slightest contamination would spoil it. The cane was first passed through the first and second rolder and then passed back again through the second and third rolder. The pressed cane was put in a baksie (basket) by a woman and carried to the trasloods. The likker flowed through a wooden trough to a large wooden cask (sisser). At the end of the trough a copper sieve had been installed to catch the dirt, which had to be cleaned continuously. In the sisser some quicklime was added to aid purification. The likker was poured through a copper sieve into the first kettle (inneemketel). When it was heated, a dirty froth appeared on top, a process that was expedited by adding more quicklime. It was strained off with a copper skimmer. The froth was diverted to the stijlhuis by a separate through. When the likker had been heated sufficiently, it was transferred to the second kettle, where more forth was produced. In the third kettle the frothing should stop. Between the first and third kettle the likker lost 4/5 of its weight.

The most competent sugar boiler was stationed near the test. He had to decide whether the likker had boiled long enough. This was a pivotal decision, because when the likker was cooked too long, it became too dark and could get a bitter taste and if it was not cooked long enough, it yielded too little sugar and too much molasses upon cooling. The smaller the test, the better the quality of the sugar. A regular test delivered about 300 pounds of sugar in one go.

When the likker had been boiled to the consistency of syrup, it was spooned into wooden casks (koelders) and left to cool while being stirred from time to time. When the mass was ‘hand warm’, it was transferred to barrels with holes in the bottom. These were put on top of a barbecot (wooden grating), so the molasses could drip out (laxeeren). It was gathered in a molasses cask underground. This process took about six weeks. The resulting sugar was rather crude and called muscovado sugar. A part was refined further to white sugar for interior use. The muscovado sugar was shipped to Europe after control by the keurmeesters. This control had been made obligatory after some planters had cheated during the curing process in the early period, for example by adding train- or lamp-oil, which spoiled the taste of the sugar.

The froth was used in the stijlhuis to distill dram (high octane rum). It was possible to use molasses, but this was rarely done in Surinam. The froth was gathered in a kettle, transferred to a large cask, covered and left to ferment for a couple of days. As a result, the dirt rose to the top and could be skimmed off. The remaining juice was poured into the distillation kettle and heated. The vapor was led through a tube, which passed through a stone cistern filled with cold water. The first liquor produced was called voorloop, then the dram condensed and the process finished with faints called loowijn. When the latter was distilled again, the result was an even fierier drink called kilduyvel (kilthum). With every hogshead of sugar cured came four jugs of dram and four jugs of molasses.

To be put to work on a sugar plantation was regarded by the slaves as the worst possible deal. Much of the pressure they suffered was the result of economic necessity. Sugar plantations could gain much by the economics of scale: it was easier to produce 700 hogsheads of sugar with 300 slaves than 200 hogsheads with 100 slaves, Teenstra maintained. Most Surinam sugar esates were undermanned and this was most keenly felt during the harvest season. Once the cane was ripe, no delay was possible. It had to be cut immediately, or the juice would spoil. After the cane had been cut, it had to be processed speedily, although Teenstra claimed it could keep for about six days in favorable weather. If it was left too long, the juice would turn sour. Consequently, it was not feasible to spread the workload evenly over the year. The harvest period lasted from four to six months and during this period a water-mill could only function once (seldom twice) a month for about nine days on end. Two times a day cane was pressed for 4 to 5 hours. Depending on the number of slaves on a plantation two or three spellen (teams) were formed, which had to work through the night in turn. Therefore, slaves had to stomach three to nine nightshifts a month. On some archaic estates nightshifts might be demanded of them on two out of every three nights.

In Blom's opinion, a field slave on a sugar plantation could cultivate 4,5 acre in cane and provisions at most, though on many plantations they had to tend more. In the 19th century, 5 acres was considered the minimum. This augmentation of the workload was mitigated somewhat by reducing maintenance work, but it is certain that with regard to the workload the slaves of the 19th century were no better off than their predecessors, in spite of the improvements in technology.

In his description of a ‘typical’ sugar estate, Blom included a sketch of the personnel needed. For a plantation of 1600 acres with a water-driven mill, producing 500 hogsheads of sugar a year, this amounted to a slave force consisting of: 100 field hands, 4 drivers, 3 provision guards, 8 carpenters, 2 masons, 6 coopers, 2 nurses, 1 fisherman and hunter, 1 cow guard, 2 gardeners, and 5 house maids. An additional 4 slaves would be ‘commanded’ by the authorities, 32 were unable to work due to illness or old age and there were 62 children. Hence a total of 232 slaves. [In reality, a plantation of this size was hardly likely to have such a large slave force.] A smaller plantation with a beestewerk, producing 250 hogsheads of sugar needed in his opinion: 50 field hands, 2 drivers, 2 provision guards, 4 carpenters, 1 mason, 3 coopers, 1 nurse, 1 fisherman and hunter, 2 cow guards, 2 grass cutters, 2 gardeners, 5 house maids. Furthermore, 2 slaves were ‘commanded’, 14 were too old or ill to be of any use and 28 were too young. As a rule, the smaller the plantation, the smaller the proportion of slaves engaged in fieldwork, because for some tasks outside the field (particularly housework) a certain minimum number of participants were deemed necessary. Consequently, the other slaves were taxed heavier.

Apart from the threats to the health of the slaves posed by nightshifts, the life on sugar plantations had other dangers as well. Cutting cane was backbreaking work and tired slaves sometimes mistook their own leg for a stalk. The sharp edges of the cane cut into their hands and feet. The work in the mill was even more risky. When pressing cane, a slave could easily get caught by the rolders. Therefore, the slaves laboring in the mill were forbidden to wear torn clothing and they often bared their torso to avoid being grabbed by the rolders and pulled between them. Sometimes they were obliged to smoke a pipe all the time to help them stay awake. Nevertheless, many a slave, because of carelessness or exhaustion, had “his bones crushed creakingly”. In some cases the whole body, except the skull, was dragged through, but in most instances the damage was restricted to hands and arms by a drastic measure: usually an axe waited within reach to chop off the trapped limb immediately. In later times, many mills were outfitted with an emergency door. If one of the workers was grabbed, the door was lowered at once, cutting off the water supply to the mill and causing the wheels to stop abruptly. The pressure of the water made them turn the other way, so the limb was released. During boiling, accidents were plentiful as well. Many slaves suffered severe burns and sometimes an unfortunate suikerkoker slipped, fell into the hot likker and died miserably.

Other hazards were far from accidental. Stedman claimed that slaves who tasted the likker too often were sometimes punished by having their tongues cut out. I venture to say that he exaggerated a bit. Although the planters did try to keep the slaves from imbibing excessively liberal doses of likker or dram, they would almost always limit their corrective measures to a sound whipping. Moreover, the slaves were allowed to chew on pieces of the “strengthening cane” as often as they pleased.

Coffee plantations.

On coffee grounds, the soil was initially prepared in nearly the same way as has been described before. Except in cases where the soil was meager, provisions were grown for a couple of years. After they were removed, the earth was turned over, the beds were laid out and new trenches were dug. The size of the beds was similar to those on sugar plantations. In each bed three to four rows of young coffee shoots were planted. Plantains were put between them to provide shade and if the soil was especially fertile, corn could be added to the mix. After four to five years, the trees were sufficiently grown and the plantains were torn out.

When the young plants were a month old, the slaves went in to weed for the first time. This task had to be repeated every six weeks. The weeds were uprooted with a hoe and left in the field to rot. At the same time, dead wood and vines (vogelkaka) were removed. When the trees were mature, weeding was only necessary every three months. In the rainy seasons the dead trees were replaced and every three to four years the trenches were deepened.

Coffee was generally picked in April/May and October/November, but these periods could vary considerably. In years of abundance, a campaign might take 10 to 12 weeks. When the trees were heavy with berries, one picker could harvest the equivalent of 15 to 20 pounds of clean coffee a day. For each pound of clean coffee he had to pick six pounds of berries. Usually a merk consisted of a certain amount of coffee, measured in baskets, which had to be picked each day. During bad years, the number of baskets demanded was too large and even if the slaves strained themselves to the utmost, they could gather no more than the equivalent of four to six pounds of clean coffee a day. The berries had to be carried home on the head, sometimes necessitating an hour’s walk with a load of nearly 100 pounds.

The harvested berries were taken to the coffee shed, which was surrounded by a floor of grey tiles (drogery). First, the red hull had to be broken by a breekmolen. When this machine was not available, the slaves cracked the hulls between their hands or pounded them with stones. Next, the beans were rubbed with water through a sieve (menarie), till they fell through the holes. They were still covered with slime that had to be removed first. To this end, they were put in a basin with water, where they stayed the night over. The next morning more water was added and the mixture was stirred. Sometimes this procedure had to be repeated several times before the slime was gone. The beans were then brought to the drogery and spread on the floor. There they were dried by sun and wind while being turned over regularly with a broom (sibi). When they were dry, they were carried to the attic for curing. They were stirred every morning and evening to avoid fermentation. Before further processing, they were deposited in the drogery for another three days, till they were hard as stones.

Next, the dried beans were pounded in the coffy mat (either a single mortar made from a large stone, or the trunk of a tree in which 10 to 20 holes had been drilled). This work was done in the evening, after the slaves had returned from the fields. Because they were locked in to keep them from stealing, it often became intolerably hot and dusty in the shed. Every mortar was worked by two slaves, who pounded in turn. A girl took out the beans when they were ready and another refilled the mortar. The finished beans were brought to a waaymolen (a funnel with a fan beneath). They fell through the funnel, while the fan blew the hulls away. Then they were either winnowed or sieved. Finally, they were spread out on large grates and sickly slaves, or women who had just given birth, sorted out the broken beans (pieken). A slave could sort about 100 pounds of coffee a day. Finally, the beans, now displaying a bright blue color, were packed in bales and ready for shipping.

The work on coffee plantations was considerably less arduous than the toil on sugar estates. The changes of falling victim to an accident were also less pronounced. For this reason, it was easier for the planters to hire additional labor during the harvest period, because the owners were less afraid to risk their valuable slaves. Since the coffee estates suffered more from the recession than the other plantations, the scarcity of personnel was aggravated during the 19th century. The solution for this problem was sought in the neglect of the coffee trees, so the slaves were hardly ever driven beyond endurance.

Blom has also provided a sketch of several ‘typical’ coffee grounds. The most elaborate estate he could imagine had 1000 acres and produced 195,000 pounds of coffee a year. It needed 108 field hands, who each tended 4 acres, 3 drivers, 3 provision guards, 5 carpenters, 3 coopers, 2 masons, 2 nurses, 2 gardeners, 1 fishermen and hunter, and 5 house servants, while 5 slaves were commanded, 36 were old or infirm and there were 77 children. Few real coffee grounds will have reached such impressive proportions. The average estate was probably closer to the second example provided by Blom (a plantation producing 95,000 pounds of coffee with 124 slaves).

Cotton plantations.

Cotton was an undemanding crop. After provisions had been grown on fresh soils for a couple of years, the first planting of cotton shoots was done in the rainy season, preferably by the end of December or the beginning of January. Three to four rows of cotton were planted in each bed. Weeding had to be done every five to six weeks and the scrubs had to be pruned every rainy season, but otherwise they needed little pampering. A cotton scrub could last for 25 to 30 years. Then it had to be cut, because otherwise the soil was damaged too much. Every four to five years the trenches were deepened and the silt was spread on the beds. One field slave could tend five to six acres of cotton without undue effort.

The first picking commenced in September and could last till December. The second harvest, not as abundant as the first, took place in March and April. The harvest was frequently spoiled by excessive rain, caterpillars, weeds and ants. Once the bolts had opened, the cotton had to be picked soon, or the fibers would rot. The slaves had to go over the same field numerous times because the bolts opened at different moments. Each scrub yielded 0,5 to 1 pound of clean cotton a year (1 pound of clean cotton equaled 3 pounds of fibers) and a diligent slave could pick the equivalent of about 20 pounds of clean cotton a day. Sometimes, a merk of this magnitude proved to be too much and the planter had to contend himself with no more than 15 pounds, according to Teenstra. It seems some progress was made in this respect during the latter part of the 18th century, because Governor Nepveu considered 4 pounds the limit, even half of that when the bolts had not opened sufficiently. The slaves gathered the cotton in large bags that hung around their necks and it was later transferred to baskets.

The picked cotton was brought to a shed, where it was dried. Next, the seeds had to be removed. This was initially done by hand, which was a tedious job indeed. A slave could sort no more than 12 pounds a day this way. At the end of the 18th century, the cotton gin was introduced and with the help of this ingenious apparatus a slave could treble his production. Operating this machine was usually done by men. The women threw the ginned cotton on top of a sieve and beat out the remaining seeds. Sometimes, children were ordered to pick out discolored cotton. Before mechanical presses came into use, the cotton was stuffed into sacks hanging from the beams of the shed by a slave jumping up and down on it.

Blom has also given a description of the slave force of a ‘typical’ cotton plantation with 246 hands. They were divided as follows: 106 field workers, 3 drivers, 5 carpenters, 1 mason, 2 nurses, 2 gardeners, 1 cow guard, 1 fisherman and hunter, and 5 house servants; while 5 slaves were ‘commanded’, 38 too old or ill to work and there were 74 children. Although the slaves, on the whole, preferred to work on cotton plantations and seemed to thrive there, the forced concentration on very large units, which became the habit in later times, may have offset some of the positive effects of crop and climate.

Cocoa plantations.

Cocoa was by far the easiest product to cultivate. It was the bad fortune of the Surinam slaves that the revenue lagged behind that of the other cash crops so much that cocoa production remained a peripheral pursuit as long as slavery lasted. If that had not been the case, the history of Surinam slavery might have taken a very different turn.

Young cocoa plants are very vulnerable, so it was difficult to keep them alive. Often, they had to be grown in baskets for the first two months. After these initial tribulations, however, they needed little care. Parasitic plants had to be removed every couple of months and the trenches had to be raked clean of dead leaves, that was all. This level of maintenance left the slaves with a lot of spare time. Only the harvest period demanded greater efforts.

The cocoa trees bore fruit twice a year. The pods were picked or knocked of the trees in March and April and once again in July. They were raked into heaps and left in the fields for a couple of days. Then they were carried to the shed, cut open and the seeds were taken out. In the beginning of the 18th century, fermentation does not seem to have been in use, but later the still pulpy seeds were thrown together, sprinkled with water, covered with banana leaves or cloth and left to ferment for a couple of days. This way the slime could be removed easily and the beans got their characteristic violet color. After drying they were packed in bales (140 pounds) or crates (300 pounds) and were ready for shipping.

Unfortunately for the slaves, plantations with a monoculture of cocoa were always rare and by the time Blom gave his description of an ‘ideal’ cocoa plantation, they were no longer in existence. Since one slave could tend 200 cocoa trees with ease, each slave had six acres in his care in Blom’s example. Such a plantation with 1000 acres, producing 360,000 pounds of cocoa should have: 90 field hands, 3 drivers, 3 provision guards, 3 carpenters, 1 mason, 3 coopers, 2 nurses, 2 cow guards, 1 fisherman and hunter, 2 gardeners, 5 house maids, 4 slaves ‘on commando’, 30 seniors and invalids and 60 children.

Timber grounds.

Timber grounds were without any doubt the most popular of the Surinam plantations as far as the slaves were concerned. Once ‘spoiled’ by the liberties inherent in logging, slaves were useless for other occupations, because they would resist such degradation with all their might. The nature of the work itself was the prime reason for their fierce attachment, because it combined several features that defined an enjoyable task for the slaves. Firstly, they worked practically without supervision. The timber concessions were often located deep into the forest, so the slaves went there on Monday morning and returned as soon as they had finished their merk. They took along sufficient food and spent the night in makeshift huts. Often, they were ready by Thursday afternoon and could go home to relax or tend their gardens. Secondly, the work itself was heavy, but it was done in the shade instead of in the blazing sun and the assignments were extremely reasonable.

There was a considerable variation, but an ordinary merk for sawing was 18 boards of about 30 feet (or a total of 500 feet) a week per two slaves. Before the slaves could begin to saw, the trees had to be felled, the branches had to be removed and the trunks had to be squared (vierkanten). The usual merk for the latter job was 25 to 30 feet a day per slave. The outer boards of a tree were called flabbe and were reserved for the slaves. For this reason, they did not get any distributions from the master, except of clothes.

Logging was strictly men’s work. The women had to carry the finished boards on their head to the master’s house, or to the river bank if the concession was too deep in the forest. They usually made two trips a day. Children under 20 years of age were not sent into the forest and presumably spent most of the day in idleness. Apart from the fact that the slaves had at least one day a week to work in their provision grounds, they were also given one free month a year to clear new grounds. The work seemed to agree with them, for the slaves on timber grounds were generally healthy looking, well muscled and bore and raised many children.

Government plantations.

Ironically, the most profitable products entailed the most tedious, tiring and unhealthy work. Since Surinam slaveholders rarely made rational business calculations, whereby they took the depreciation of the value of their slave force and their land into consideration, they practically always opted for a quick gain and chose the product that yielded the most profit in the least time. Only if they had little capital to invest and were unable to borrow it, or if they had exhausted their land beyond redemption, they switched to less profitable crops.

Only one group of slaves did not suffer from the dictatorship of the desire for speedy profit: the slaves owned by the Society of Surinam. From the beginning the Society exploited plantations of its own, but making a profit was only a secondary motive. In the early period of its rule, the main objective was to grow food for the slaves awaiting sale and for the slaves of the Society themselves. This was necessary because the private plantations could not even feed their own slaves, let alone provide a surplus. Later, the provision grounds of the Society were abandoned, except for some fields that were used for agricultural experiments. Some slaves of the Society labored in the stone quarry Worsteling Jacobs, which was not a very rewarding business. Consequently, the slaves were kept busy, but did not exactly overexert themselves. The Society and its employees also displayed a much more paternalistic ethos than most of the private entrepreneurs.

The Dutch government found itself the reluctant owner of several plantations during the 19th century. These were mostly sugar and coffee estates and were supposed to be run as a normal enterprise, preferably yielding a profit. In reality, their opportunities far surpassed those of the private plantations. They were granted money for costly innovations that greatly lightened the burdens of the slaves. Moreover, the government regulations regarding the workload and the distributions were strictly enforced. The inevitable losses were covered by government subsidies. For the slaves, being put to work on these estates meant the first prize in the plantation lottery. They were much envied by their less fortunate colleagues, for whom there was little chance of substantially improving their lot as long as shortsighted capitalism reigned.

Alternative work.

The majority of the plantation slaves were actual or potential field hands. However, a considerable minority managed to escape the fields temporarily or permanently. The percentage could fluctuate considerably, because the number of slaves actually working in these jobs was not determined by economic reasons alone.

Take for example the house servants. Blom invariably reserved five slaves for this job, whether the plantation was large or small. He may have been partly correct, for the division of labor necessitated a minimum number of servants (a cook, a washerwoman, a valet, etc.), but a more important determinant was the number of whites present and the demands they made. When the owner and his family were residing on the plantation, the number of servants exploded. Some directors had a large ‘harem’ and rewarded their concubines with cushy jobs in the Big House. Remarkably, owners and administrators hardly ever interfered, even when a director took slaves from the field merely for his own pleasure.

The number of non-field slaves also depended on the number of bondsmen with mixed blood on a plantation. They could not be sent into the field, so other tasks had to be found, or if necessary created, for them. Few slaves lighter than mulattoes remained on the plantations, they were nearly always dispatched to Paramaribo, perhaps because the less sophisticated crafts were deemed beneath their station and no jobs carrying sufficient prestige were available.

The most prestigious position, driver (bastiaan or basja), could never be theirs. Bastiaans were nearly always full-blooded Negroes and often Africans, who were believed to be better able to handle recalcitrant subordinates. With the exception of the smallest ones, plantations usually had two or three drivers. On coffee grounds there was usually a field driver and a loodsbastiaan, who often doubled as dresneger (nurse). The slaves chosen for this job were often in their early thirties, had a reputation as a good, dependable worker and were able to dominate the other slaves without having to rely on the support of a white. This implied that they were physically strong and had no scruples about using violence. In return for their loyalty, the bastiaans did not have to perform manual labor and they were granted coveted privileges. They received larger rations and a greater share of the other distributions; they were permitted to have a separate cabin when others were not; they were allowed to marry more than one woman, etc. However, they were not able to keep themselves aloof from the other slaves the way the (mulatto) house servants and artisans often were. They lived among the field slaves, they intermarried with them and they had to face their anger if they abused their privileges.

The bastiaans were in the best position to enrich themselves. They sometimes forced their underlings to work for them and pocketed the proceeds. Meanwhile, they prodded the other slaves harder to finish the abandoned tasks. This was a regular habit with some of the drivers working on Fort Nieuw Amsterdam. Many slaves resented this kind of exploitation and they did all they could to rid themselves of their tormentor. Others, however, seemed to have accepted this abuse as their due -like the tribute they would pay a chief. Bartelink, for example, observed on his plantation that some of the slaves were not where they were supposed to be. He wanted to make an end to this ‘loafing’ immediately, but an old slave woman stopped him before he could make a fool of himself: “’If you do this you, will be irretrievably lost’, she told me; ‘the two men have gone to fish for the head bastiaan or to work on his provision ground. You will have him as well as the people against you. If you wait you will see, that the others will finish the two merken of the absentees in their free time”. And indeed, it happened exactly as she had predicted.

Eugene Genovese has devoted many pages to the ambiguous situation of the driver in the Old South. He emphatically disagreed with the writers that portrayed drivers as Uncle Toms -men who betrayed their people for material gains and whose cruelty against their fellow slaves was just as despicable as that of the white overseers. He pointed out that drivers were often intermediates between masters and slaves and bore the brunt of the dissatisfaction of both parties. Genovese was convinced that most drivers not only tried to help their people as best as they could, but that they would not hesitate to lead them into rebellion if the lines were crossed too often.

In Surinam the situation was no different. Up to a point, the slaves had to swallow the abuse of a harsh driver, because he was backed by the authority of the master, but they had a powerful weapon at their disposition. Most plantations were plagued by scores of mysterious deaths, which greatly worried the directors as they were held responsible. Many a hated driver found himself denounced as a ‘poisoner’ by vengeful fellow slaves, who often built up such a convincing case that even the most skeptic director started to have doubts. In the 17th and early 18th centuries especially, the Court of Police took these accusations seriously and often convicted an accused on the shallowest evidence. The driver who escaped such a court case with his head still on his shoulders could consider himself lucky and no doubt returned to the plantation a chastised man. In other cases, unpopular drivers were attacked and severely beaten, or even killed by their irate victims.

In many cases it turned out that bastiaans had close contacts with Maroons, or planned and led rebellions. They were eminently suited for such a role. Not only was their freedom of movement greater, but they were also in a position to command the participation of the other slaves, even if these were not very eager to risk their necks. For this reason, Maroons who wanted to enlist plantation slaves in their army often sought out the drivers first. That some bastiaans were eager to comply had a simple reason. The primary motive for rebellion was the loss of privileges and the bastiaans were among the few slaves who had really something to lose.

The position of the artisans was often even more ambiguous. Many of them were of mixed descent. On some plantations there were black artisans only, but even they had usually not been dragged from the field, but had been selected as youths and had spent most of their life in the close proximity of whites. In the beginning of the slavery era, they were apprenticed to a white tradesman and often continued to work under his supervision. Later in the 18th century, white artisans became increasingly rare on plantations and the slaves worked largely on their own. To the surprise of their superiors, they frequently did exceptionally well. Salomon Sanders, a director of the Bergwerk, reported after buying 18 slaves: “I have put Three of Those Slaves to Carpentry, And They have done the Whole Work again, Without having A White Carpenter Present, Also [I put] One with the Smith the Same Way, And One with the Mason, Who Shall also Be Capable in a short time, So They can Do their Work Alone, Without having A Boss Present”.

It is difficult to give any indication of the number of craftsmen on the average estate. A sugar plantation clearly needed more than other kinds of plantations of similar size (a fact overlooked by Blom), but an estimate of 10% of the field force would not be far off the mark. A run-of-the-mill plantation needed at least two carpenters, a mason, some coopers, a nurse, etc.

The planters had more trouble with outlining the merken for tradesmen than for field hands. Most plantations dispensed with them entirely and the directors just gave ad-hoc orders every day. On some plantations, however, attempts at establishing proper assignments were made. There, carpenters had to repair a boat within a specified time, or coopers had to finish a certain number of barrels each week.